Want to understand your customer? Ask!

A core concept in our grow-smart strategy is to lead with the customer. Project #1 asked you to think like your customer, to consider what they care about. But even that can only take you so far; it’s still your opinion, after all.

So, to really know how customers think, you’ve got to ask.

Why not a survey?

Surveys are great, but they work best for existing products and services, or those close to launch. At that point, you can focus on questions such as pricing, features, competition and the customer’s view of these issues. This can be very helpful in setting pricing, customer targeting and marketing messaging.

It’s less effective when the service or product is still in the planning stages:

- The customer’s reaction will be based predominantly – or solely – on your no-doubt glowing description, as there’s nothing else for them to evaluate

- The customer has no “skin in the game.” Why not say nice things? They’re not going to be asked to buy it.

- They may, indeed, think highly of the idea, but that’s no indication of buying intent. To understand that, you need to know more about their motivation and process.

That’s where customer discovery comes in.

Why buy?

Customer discovery focuses more on motivation and process:

- Who is the customer?

- How do they currently handle whatever task your business hopes to help them with?

- What works that they’re doing now and what doesn’t?

- How bothersome are the things that aren’t working; is it worth switching?

- If they were to switch, how would they go about doing so? What’s the process and why do they ultimately decide to buy?

Buyer roles

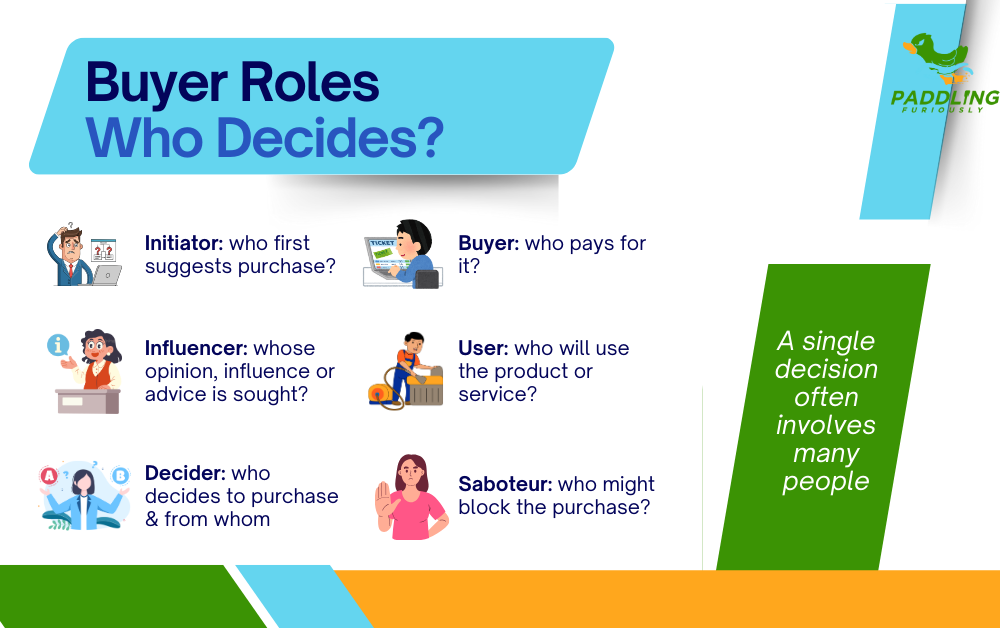

Some transactions are impulse purchases; far more are the result of research and planning. Often, that process involves multiple people in various roles. Understanding who’s likely to be involved in your buying process is crucial in everything from product design through launch strategy, targeting, pricing and support.

Customer discovery: test your theories

Of course, you could develop whatever you think is best and learn from feedback. There’s value in this; that’s why people build prototypes or launch an MVP version. But wouldn’t it be nice to get some sense you’re on the right track before going to all that time and expense?

Customer discovery can help you with this. You start by creating a hypothesis, which you then test through conversations with people who might be involved in your business: customers, suppliers, channel partners and others.

Actually, you create two hypotheses:

Problem hypothesis: What problem is the customer trying to solve and how do they experience it? Knowing if and how they discuss the issue will help you understand its significance to them, as well as the particular challenges that might motivate them to change.

- How does the customer see the problem? How significant is it?

- How are they solving it now, and how motivated are they to change?

- If they were to consider an alternative, what would they want or need to know in order to make the change?

Solution hypothesis: The solution here is NOT your product or service. Instead, you want to think back to the value proposition:

- What is your customer trying to accomplish or avoid?

- How does your product or service aid the customer in achieving these goals?

Talk, but listen even more

Now it’s time to test – and, more importantly – revise your hypotheses. To do this, you’re going to talk to people: potential customers, suppliers, buyers, users, saboteurs and others involved in the process. The goal is to get a broad range of opinions.

That breadth applies not just to whom you ask, but also to how you ask. Ideally, these are open-ended discussions that focus on understanding the customer’s experience of the broader environment in which your solution might be helpful: their job, if you’re B2B, their buying habits, hobbies etc in B2C. What works about their current approach; what doesn’t? Let them talk – you’re here to listen.

Listen for things you don’t want to hear: “confirmation bias” describes our natural inclination to respond to things we expect or want to hear. Opportunities for confirmation bias abound in these conversations – even more so, as it’s tempting to steer the discussion in a hoped-for direction. Try hard to avoid this.

Follow unexpected digressions: While it’s encouraging to have your opinions confirmed, it’s far more valuable to follow up on comments that surprise or confound you. This is where you’ll uncover flaws in your thesis – or, potentially, discover ideas or issues that may be even more compelling than your original thesis.

Have as many conversations as you can. Listen, learn, revise your thesis and repeat.

What do you really need to know?

The goal of customer discovery is to test before you build, to learn as much as you can so you don’t waste time and money on a product no one wants.

The whole process can be very extensive; many customer discovery experts recommend 100 or more interviews. That’s great, if you can do it, but not everyone can.

So we’ve devised a framework to help you focus on the key questions, the central tenets of your product or service that [contain] the greatest uncertainty. You can learn more about our framework and access a worksheet to help you here.

Access our free worksheet here (access for logged-in users only — registration is free)

Note: learn more about Customer Discovery

Many experts have written on the Customer Discover framework. If you’re interested in learning more, here are good places to start:

- Customer Discovery Handbook (Alexander Cowen)

- Steve Blank / YouTube (customer discovery; 24-video series)